How Big Tech maintains its dominance

As Big Tech deepens its dominance into new public domains, major issues arise around fundamental rights, democracy and justice.

by Sarah Chander, EDRi

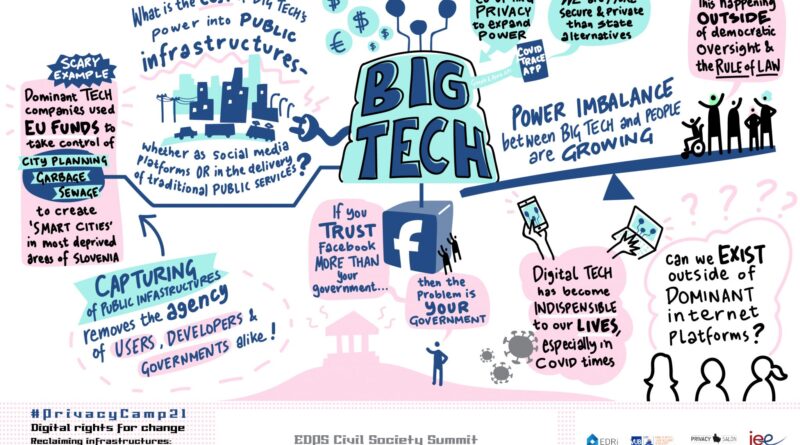

Big Tech’s “power-grabs” in public domains such as healthcare, education, and public administration have huge implications on our individual rights – but will also fundamentally alter what is “public” in our societies. Big Tech’s dominance once maintained through data extraction from its user base on large platforms has now shifted, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, expanding the reach of technology companies deeper into “public domains”. Understanding exactly how this is happening will impact how we contest it.

What are the concepts, tools, and methods we need to challenge Big Tech? In the face of its shifting expansion, we need to fight for structural solutions to the dominance of corporations.

Every year at its annual event Privacy Camp, EDRi discusses a major issue of digital rights with the European Data Protection Supervisor at the Civil Society Summit. Big Tech’s growing dominance in the public sphere was the focus of the 2021 session. Our panellists came to the issue from different angles; concerning freedom of expression on social media platforms (Gabrielle Guillemin, Article 19) the involvement of technology companies in “Smart Cities” (Domen Savič, Državljan D) and the mechanics of how technology companies have secured their power through computational infrastructures (Dr Seda Gürses, TU Delft.) These considerations were reflected the responses of Wojciech Wiewiórowski, The European Data Protection Supervisor, questioning what is the public sphere today and how EU regulation can adjust to new frontiers.

How Big Tech dominates

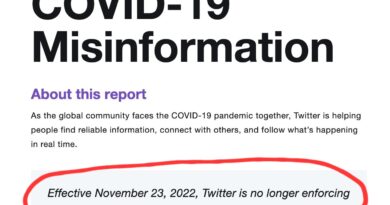

The opaque ways in which technology companies moderate public debates online demonstrate their ever-increasing power. The removal of chat and social apps like Element, Telegram, or even Parler are power moves showing that, despite the “public”, global and widespread user-base of those apps, the corporations decide the rules of the game, including free speech. This – along with increasing awareness of how companies’ data-intensive advertising model exploits our personal data and amplifies hate speech and disinformation – has started a global conversation about how to reign in tech companies.

However, the domination doesn’t stop at our speech and data. The technology industry, estimated at a value of over $6 trillion – and is now more valuable than the entire European stock market, according to a Bank of America Global research – has expanded its reach far beyond social media. The growth of this industry was fuelled heavily by finance following the 2008 crash. Now, companies must grow to provide returns – and this growth model necessitates expansion.

This expansion comes in several forms. One, as uncovered by the Tracking Smart Cities project in Slovenia, involves the provision of infrastructure to public institutions. Often offered at little or no-cost, or funded by research and innovation projects like the EU’s Horizon 2020, companies are able to capture the market by providing technical ‘solutions’ to social problems. In small, often poor, cities in Slovenia, small-scale issues like rat infestations and rubbish disposal has been offered up for private involvement via “Smart Tech”. Whilst these may seem like small-scale interventions, we see the same trends replicated elsewhere in areas such as security, policing and migration, with a vast potential for human rights breaches and discrimination. The full potential extent and impact of private sector involvement in these fields was exposed this week in the Frontex Files.

The other way companies leverage power is through computational infrastructures. By providing clouds, mobile devices, chips and application programming interfaces (APIs) as the basis for all software development, power has been concentrated at the hands of a few major corporations with infrastructures and processing power. Not only is this invasive in terms of processing of individuals’ personal data, it necessarily requires that all software development must go through these major tech companies.

Privacy and (infrastructural) power

These trends have exacerbated a cycle of hyper-dependence, power asymmetry and control over users, developers and increasingly, public institutions. During the development of Contact Tracing Apps during the summer of 2020, Google and Apple demonstrated this dominance over governments by choosing to integrate the contract tracing platform into their operating systems.

Not only was this a vast display of these companies’ infrastructural power, Seda Gürses highlighted how this move challenged the very tools we have used to contest this dominance: privacy.

“We thought that privacy could limit the accumulation of data, but they are so dominant, they could use privacy as power. It is a path to power for Big Tech.” – Seda Gürses

Apple and Google used “privacy by design” as an argument for positioning themselves between users and governments. They said “we can do it better” and governments had no choice but to follow suit. This power move highlighted for many that safeguarding privacy was not the major issue here – it was the vast, infrastructural, concentrated power of Big Tech. In response, the question is not only, “how can we ensure our privacy” but rather, “how can we contest Big Tech’s dominance?”

How do we contest Big Tech?

Understanding that data protection and privacy in themselves will not be sufficient to reverse the trend, we discussed what other tools we might need. Exploring ongoing initiatives at the European Union level, we recognised opportunities and limits.

The proposed Digital Services Act and Digital Market Acts package and upcoming EU legislative proposals on artificial intelligence may propose some answers. However, insofar as the former presents more obligations on companies, there is a risk of reinforcing their power and position as the arbiter of acceptable content online:

“The largest platforms clearly need to be more transparent and accountable to their users and the public. At the same time, it is vital that obligations in the DSA or other platform regulatory framworks do not reinforce the dominance of these platforms” – Gabrielle Guillemin.

Competition mechanisms can only be useful to the extent that they truly address the infrastructural power of these companies. The goal should not be to ensure more companies can exercise dominance, but rather to limit the dominance itself.

Upcoming proposals on artificial intelligence, along with discourses of ‘tech for good’ and ‘ethical AI’ must not detract from the broader issue of capital concentrated in the hands of the few. Much of the dangers presented by artificial intelligence has been to create a supply and demand for ‘technical solutions’ to complicated social problems, often with vast potential harms for society and the most marginalised within. If contesting dominance is the goal, we must also challenge the vast funding offered to private companies through programs such as Horizon 2020 further instilling digitalisation monopolies.

Beyond individual rights to broader struggles for justice

At a movement level, we have learned that tech companies have co-opted and de-politicised the very concepts, safeguards and protections we have fought for to safeguard our rights, such as privacy and data protection. Looking critically, we increasingly see the limits of these frameworks to halt Big Tech’s dominance.

“The “active citizen” or consumer should not be pushed too far – we can’t do everything. Putting the responsibility to the end user is not going to work.” – Domen Savič

One key reason is that they place the burden on individuals to contest issues of vast scale political power. As recently demonstrated by NOYB in its press statement following the Hamburg Data Protection Authority’s decision not to issue a pan-European order against Clearview AI:

“Every European would have to submit their own complaint against Clearview AI in order to not be included in the search results of their biometric database. Not only is this inefficient, it is also an unnecessary burden for Europeans who must actively take steps to have their profile removed from Clearview AI’s biometric database, even though the collection of such data is already illegal from the get go.”

We need to demand more than legal frameworks that place the burden for contesting harms on the shoulders of individuals. We cannot simply hope that dominant corporations will benevolently opt to uphold individual rights even if this threatens their market power and profits. Even with regulation, this has been tricky, to say the least.

With this in mind, we need to re-orient the conversation back to one of contesting dominance and achieving justice. In the words of Wendy Brown, we need to reclaim the “vocabularies of power” necessary to make this dominance visible. As this dominance unfolds, it must be re-politicised and the conversation focused on what is materially at stake.

This means firmly situating digital rights into broader struggles for justice, whether it be contesting how the surveillance industry profits from the criminalisation of migrants and racialised communities; halting investment in “innovations” which only deepen the influence of corporations, and committing to models of governance that put public decisions and resources back into the hands of people.

This article is republished from EDRi under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.